Elden Johnson points out features of the trans-Alaska pipeline north of Fairbanks on July 1, 2008. Photo by Ned Rozell.

Elden Johnson points out features of the trans-Alaska pipeline north of Fairbanks on July 1, 2008. Photo by Ned Rozell.

Story by Ned Rozell

In 1973, Elden Johnson was a young engineer working on one of the most ambitious and uncertain projects in the world — an 800-mile steel pipeline that carried warm oil over frozen ground. Decades later, Johnson looked back at what he called “the greatest story ever told of man’s interaction with permafrost.”

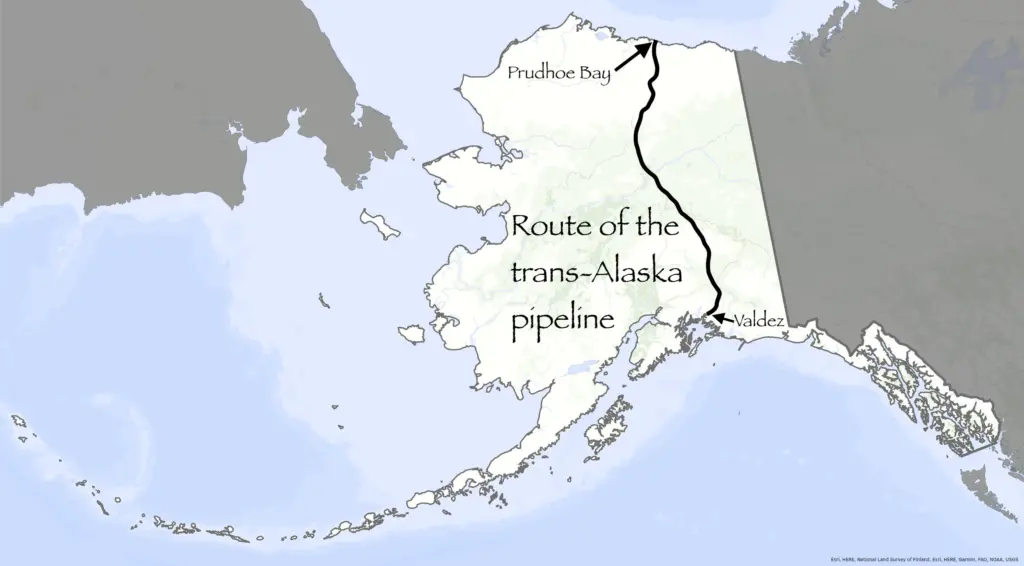

Strung over and beneath the surface of Alaska from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez, the trans-Alaska pipeline is well into its second lifetime. The four-foot in diameter, half-inch-thick steel pipe had an original design lifespan of 30 years. The State of Alaska and the U.S. Department of the Interior gave the pipeline the green light for another 30 years of operation.

“It’s like a car,” said Johnson, while standing under the pipeline near Fairbanks during a permafrost-conference lecture in 2008. “As long as you maintain it, it’ll continue to work.”

Permafrost, frozen ground that is a relic of the last ice age, exists beneath about 75 percent of the pipeline’s 800-mile route. When ice-rich permafrost thaws, the ground slumps, causing problems for structures above.

A section of above-ground trans-Alaska pipeline follows the landscape near the Klutina River south of Glennallen. Photo by Ned Rozell.

A section of above-ground trans-Alaska pipeline follows the landscape near the Klutina River south of Glennallen. Photo by Ned Rozell.

After the 1969 oil discovery at Prudhoe Bay, developers unfamiliar with Alaska wanted to bury the entire supply of made-in-Japan pipe. After a review by people who knew the dangers of building on permafrost, a legion of workers constructed a pipeline buried for 380 miles and — in areas of permafrost — built above the ground on platforms for 420 miles.

The initial design was good, but not perfect, Johnson said. He remembered during construction when he and others were inspecting the ground from the Yukon River to Coldfoot. They found unstable permafrost and recommended re-design of sections of the pipeline. Instead of conventional buried pipeline, the engineers called for more expensive and time-consumptive, above-ground pipeline.

“We changed the design for at least 20 percent of that distance,” said Johnson, who worked for Alyeska Pipeline Service Company before retiring from there in 2008. “They were gut-wrenching decisions potentially impacting the startup schedule.”

The call to elevate more than half the pipeline turned out to be a good one. Even though engineers bored holes in the ground about every 800 feet to check for permafrost, they didn’t find it all.

When the pipeline was two years old in 1979, the pipe buckled and leaked in two buried sections because of thawed permafrost. In both cases, the pipeline, which carried oil that left the ground in Prudhoe Bay as warm as 145 degrees Fahrenheit, caused about four feet of settlement. Engineers fixed those and other problems.

A section of below-ground trans-Alaska pipeline is buried beneath a south-facing hillside near the Salcha River. Photo by Ned Rozell.

A section of below-ground trans-Alaska pipeline is buried beneath a south-facing hillside near the Salcha River. Photo by Ned Rozell.

Alyeska contractors check the pipeline for signs of settling and proper operation of the heat pipes that help keep the support posts of the above-ground pipeline anchored in frozen ground. The buried pipeline has become more stable as the rapid thawing of early years has settled down.

“The risk to the buried pipeline right now is becoming minimal,” Johnson said in 2008.

The pipeline has delivered more than 18 billion barrels of oil since its startup in June 1977, with two brief shutdowns due to permafrost. Johnson estimated permafrost-related maintenance had totaled about 5-to-10 percent of the operating costs over the life of the pipeline.

“It’s the cost of doing business in the Arctic,” he said.